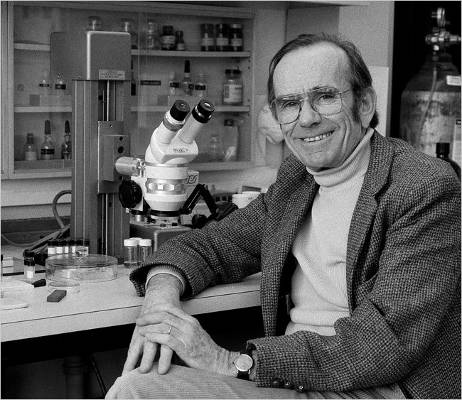

Thomas Eisner (1929 - 2011)

Thomas Eisner, a father of chemical ecology, in his Cornell lab in 1988. Photo by Michael J. Okoniewski

"I simply imagined how the component parts of a given arrangement

might fit together, and laid out the parts in accord with the vision.

It was like playing with a Lego set."

T. Eisner, 2006

might fit together, and laid out the parts in accord with the vision.

It was like playing with a Lego set."

T. Eisner, 2006

Thomas Eisner, a groundbreaking authority on insects whose research revealed the complex chemistry that they use to repel predators, attract mates and protect their young, died on Friday at his home in Ithaca, N.Y. He was 81.

The cause was complications of Parkinson's disease, said Cornell University, where he had been a professor of chemical ecology.

In the introduction to Dr. Eisner's 2003 book "For Love of Insects," the Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson called him "the modern Fabre," after Jean-Henri Fabre, the French pioneer of insect research.

Dr. Eisner realized early in his career that in addition to sounds and visual cues like colored markings and elaborate dances, insects often communicate through chemical signals.

Dr. Eisner and Jerrold Meinwald, a Cornell chemistry professor, are considered the fathers of a field now known as chemical ecology. They collaborated for more than half a century, deciphering the mysteries of earwigs, millipedes and many other insects.

For example, Dr. Eisner and Dr. Meinwald showed how male bella moths used plant toxins to attract mates.

Dr. Eisner was actually studying a different insect - orb-weaving spiders - when he noticed a brightly colored moth flying in a web. The spider, instead of pouncing on the moth and eating it, cut it out and set it free. Intrigued, he caught more bella moths and threw them into the web. The spider set them free, too.

To understand why, Dr. Eisner and Dr. Meinwald studied the bella moth more closely. They found that the males carried distasteful chemicals known as alkaloids that they had ingested as larvae from plants. The alkaloids leave a very bad taste for spiders and other creatures that would eat the moths.

Further, the scientists observed that female moths found the toxins attractive. When they mated, the male bestowed the alkaloids to its mate, which then passed them to the eggs, making the offspring less tasty and more likely to survive.

"The father is able to protect the next generation chemically," Dr. Meinwald said. "That's one story both Tom and I liked."

Thomas D. Seeley, a Cornell biologist, said Dr. Eisner and Dr. Meinwald "really did open this whole dimension of chemistry in the natural world."

Dr. Eisner also studied the bombardier beetle. Even before Charles Darwin studied them, biologists knew that the beetle shot out a hot liquid as a defense mechanism. But they did not know how the beetle did it or what it was shooting.

In his research, Dr. Eisner and his colleagues showed that the beetle, in effect, makes a form of rocket fuel - boiling hot, no less - by combining two separately stored chemicals, then steers the stream by rotating the tip of its abdomen.

"Insects are the most versatile chemists on Earth," Dr. Eisner said in a 1989 interview.

Thomas Eisner was born in Berlin on June 25, 1929. His family was Jewish and moved to Barcelona, Spain, in 1933 when Hitler came to power in Germany. The violence of the Spanish Civil War led them to move to Uruguay, where, Dr. Eisner recalled, he was surrounded by a panoply of bugs.

After the Eisners moved to the United States in 1947, he enrolled at Champlain College in Plattsburgh, N.Y., and transferred to Harvard two years later. It was at Harvard that he took his first entomology course and realized that his love of insects could grow into a career. (As Harvard graduate students, he and Professor Wilson went on a two-month road trip to collect insects around the country.)

After graduating with a bachelor's degree in 1951 and a doctorate in 1955, Dr. Eisner joined the faculty at Cornell. However, he never forgot that Cornell had rejected him as an undergraduate and displayed the rejection letter in his office.

Dr. Eisner was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and in 1994 he received a National Medal of Science, the highest scientific honor in the United States. He was also an ardent conservationist and served on the boards of the National Audubon Society, the National Scientific Council of the Nature Conservancy, the Union of Concerned Scientists and the World Resources Institute Council.

In 1991, he brokered an agreement between Merck, the pharmaceutical giant, and the National Biodiversity Institute of Costa Rica. The institute provided samples of Costa Rican plants, insects and microbes that Merck would test for possible use in new drugs. A percentage of any profits that Merck might make would go back to Costa Rica for conservation efforts. None of the 1,000 compounds that were analyzed, however, resulted in a new drug.

Dr. Eisner is survived by his wife of 58 years, Maria; three daughters, Yvonne Eisner of Pelham, N.Y., Vivian Eisner of Warwick, R.I.; and Christina Brown of Wheaton, Ill; and six grandchildren.

Dr. Eisner's life could have taken a different turn had he not listened to his piano teacher, the German conductor Fritz Busch. Though Dr. Eisner became an accomplished pianist, Busch told him he would never reach the top echelons of the music world.

Still, Dr. Eisner continued to play throughout his life, and he kept an upright piano in his laboratory.

Even as Parkinson's began to sap his physical abilities, Dr. Eisner found new avenues of expression, creating art with a color photocopier using insects, flowers and other objects and turning them into images of startling clarity.

After New York Times, March 2011

« Thomas Eisner, Who Cracked Chemistry of Bugs, Dies at 81 »

by Kenneth Chang, March 30, 2011